Artists and art lovers greatly admire his dense, atmospheric paintings: Carl Schuch (1846–1903) is perhaps the best known unknown among the great European painters of the late 19th century. Inspired by now world-famous French artists such as Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, and Gustave Courbet, he forged his own path. In his search for insight and meaning, the Vienna-born painter devoted his life entirely to art.

A unique visual experience: Carl Schuch’s artworks possess a striking, deeply resonant quality. At times harmonious, at others full of tension, his subtle colour compositions are meticulously conceived and executed.

Nuances of colour and light, foreground and background, individual motifs and the overall composition are intricately interwoven. Experiencing Schuch’s paintings in person, engaging with them, and exploring them in depth is well worth the effort.

Schuch

Searching

Already as a young man in Vienna, Carl Schuch decided to pursue an artistic career. In his quest for a unique language of colour and form, he became deeply inspired by the modern art and culture of France.

„France had gone ahead and produced masterpieces in literature and painting that have since been widely imitated but are still unmatched in any other country.“

A keen gaze upon the world, dressed in gallant black and wearing a top hat, a cigarette casually resting in the corner of his mouth: the portrait shows Carl Schuch at the age of 29. Yet the painting by Wilhelm Leibl, a companion of Schuch’s, also hints at a deep melancholy.

An inheritance from his parents made it possible: Schuch was able to afford an artistic education in Vienna. After abandoning his studies at the State Academy of Fine Arts, he took private lessons with the landscape painter Ludwig Halauska (1827–1882).

The death of his sister Pauline in 1869 prompted Carl Schuch to leave his hometown. The highly educated and polyglot young man went on a journey—through Italy, via Rome and Naples, and later also to Paris and Brussels, Amsterdam, Dresden, and Munich.

Around 1870, Europe was deeply divided politically. During a stay in Italy, Schuch witnessed the capture of Rome, which marked the end of the Italian Wars of Independence and led to the separation from the Austrian imperial crown and to national unification. At the same time, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 was raging: This conflict brought about hundreds of thousands of deaths and severe destruction. It resulted in the founding of the German Empire and the end of the Second Empire, the Second French Empire. Schuch lived in times of upheaval – In his notebooks and letters, there are frequent references to the rapid political developments of his era, yet his paintings remain untouched by these events.

While journeying across Europe, Schuch’s gaze was ever drawn toward France. In museums and galleries, his particular attention lingered on the works of contemporary French artists. He was captivated by the new wave of painting emerging from France—where, from the mid-19th century onward, artists had broken with long-established conventions. In an era of profound transformation, they championed an art that was unprejudiced and sincere.

“The French succeeded in breaking away from the traditional way of seeing and in discovering a more natural and profound relationship with nature.“

Schuch’s enthusiasm for French art had good reasons: in Paris, artists, art critics, and intellectuals had already been debating, since the mid-19th century, a new meaning and social role for painting. Under the catchwords “Naturalism” and “Realism,” the relationship between art and reality was being redefined. Paintings were no longer to be created according to the rigid rules of the state art academies. Instead, what was demanded was the individual and impartial rendering of what was seen and experienced, with the aim of an art vivant—a “living art.” Free from unnecessary embellishment and indulgent idealization, these new forms of expression were meant to do justice to the modern world.

Authentic images of nature – impactfull, yet unembellished: the new landscape art emerged at a time of widespread industrialization and urbanization in Europe.

“We paint nature today as it appears to the unbiased, unprejudiced eye. Not as we ‘know it to be.’ Naïve!”

Truthful and

Unconventional

Creating art free of preconceptions – Carl Schuch shared this vision with his contemporaries. In Munich, he became part of the artistic circle surrounding the painter Wilhelm Leibl (1844–1900). What united them was a deep admiration for French art, especially for the great Gustave Courbet (1819–1877).

Shared working hours, common pictorial motifs, and similar painting techniques: in the 1870s Carl Schuch worked in close collaboration with the artists of the Leibl-Circle. Especially with Wilhelm Trübner (1851–1917) he developed a lively and creative exchange. In so-called still lifes – depictions of arranged objects – the artists tested their painterly skills.

“[Courbet] had an incomparable advantage – he was himself, stood on his own feet, saw with his own eyes, broke all conventions (…).”

“The young people here paint entirely in my style,” wrote Gustave Courbet from Munich to his parents in 1869. Indeed, his realism and dazzling fame captivated an entire generation of artists. During his stay in Munich, Courbet was surrounded by admirers—including the circle around Wilhelm Leibl. Courbet sought an unembellished art: instead of heroes and saints, he painted farmworkers and maids; instead of conventional compositions, he pursued creative forms of representation and the artist’s individual perspective. His artistic demands went hand in hand with his political stance. When the Paris Commune rose up in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War—against both the German occupiers and Napoleon III’s government—Courbet took part. He was among the instigators of the destruction of the Vendôme Column, a symbol of the monarchy. Schuch, however, felt no affinity with the Frenchman’s political side. He once wrote that Courbet’s great talent had greatly suffered from his “combative attitude.”

“Seeing and exploring for oneself” – that was Carl Schuch’s lofty ideal. He left the established norms and genres of art – painting by rules and recipes, as taught at the state art academies – to the “careerists.”

The bank of a pond in the Upper Bavarian surroundings of Munich – with this painting Schuch contradicted the viewing habits of his time: Schuch consciously turned away from the sweeping romanticism of more traditional landscape imagery.

Inspired by Courbet’s innovations, Schuch modeled his compositions on the Frenchman’s example. In works such as this atmospheric stream landscape, the unconventional perspective and the narrow sliver of sky in the upper left corner were already foreshadowed.

Not only in France did artists in the second half of the 19th century pursue defined theoretical goals: Wilhelm Leibl, with whose circle Carl Schuch moved in Munich, declared “Reine Malerei” (“pure painting”) to be his maxim. Under the influence of Gustave Courbet, he developed the idea of an unadulterated, almost objective art that should reproduce nothing but what is seen. The focus was on form, colour, light, and materiality – in other words, on what is purely painterly. What a painting shows was less important for Leibl and his companions. They dedicated their art to the how – to colour design, brushwork, and the inner attitude of the painter.

On his journeys through Europe, Schuch surrounded himself with art and artists who enriched and inspired him. But he refused to commit to any fixed school—let alone follow trends or the demands of the art market. When the painting methods of the Leibl circle began to feel too routine, he left Bavaria and moved to Venice.

“No matter how much you may have learned (…) the virtuosity of the mind is the real talent.”

Schuch

in Venice

Venice – city of water! Carl Schuch spent the years between 1876 and 1882 in the lagoon – and encountered the place with mixed feelings.

“Venice is a swamp for me.”

In Venice Schuch lived close to the Abbazia San Gregorio, the city’s oldest monastery. In his painting of 1878 he captured the façade of the inner courtyard. With refined brush technique, he conveyed the effect of the incoming sunlight in the picture.

Today Venice is a magnet for mass tourism. In Schuch’s time the lagoon was quieter, but already attracted wealthy people, artists, and intellectuals from Europe and the world. Countless painters had immortalized the houses, canals, and gondolas of the unique city for centuries.

“I see the time coming when Venice will offer me much. Once I advance thoroughly for a few more years, can properly paint landscape and air, and water, then I will subordinate architecture and paint only in light and colour, ships, water, etc.”

Carl Schuch shied away from bringing the unique beauty of Venice to the canvas. He led the life of a bachelor and devoted himself—with great perfectionism—to his notes and colour studies in his studio.

“I now have a piano, spend much time at home, frequent all the brothels, and on the whole feel more content.” With a striking frankness by today’s standards, Schuch candidly recounts his love affairs in his notebooks and letters. Angelina, Venturina, Elena, and Marie — some names of his lovers and prostitutes have been preserved, but their life stories remain unknown. He wrote from Venice to a friend that he had “not yet contracted syphilis,” yet he eventually did fall ill with a venereal disease that tormented him painfully until his death. Schuch’s lifestyle as a lifelong bachelor was shared by many European artists, composers, and writers of the 19th century. In an era when remaining unmarried was morally frowned upon, the role of the dandy or eternal bachelor was most readily tolerated among creative men. It was not until the age of 48, already seriously ill, that Schuch married in Vienna.

Winter in the Studio

Schuch spent the winters in his Venetian studio. He read literature from France, studied works of fellow artists meticulously, and painted his own pictures – especially still lifes.

For a while, Schuch considered Lobster with Pewter Jug and Wine Glass one of his finest works, even thinking of exhibiting it. Yet nothing came of it. Public acclaim and the art market meant little to him. In fact, he is said to have sold only a single painting during his lifetime. It was only in 1904, thanks to the initiative of his friend Wilhelm Trübner, that the Lobster was shown at Eduard Schulte’s Berlin art salon—where Hugo von Tschudi, director of the Berlin Nationalgalerie, immediately purchased it for the museum.

Looking closely, exploring, and experimenting: Schuch used still life painting to examine the effect of colours under different qualities of light. How could the complex interplay of what is seen be conveyed in a painting? Schuch constantly subjected his painting strategies to new tests.

Still lifes come in all shapes and forms: During his winters in Venice, Schuch experimented with larger formats, which he later rejected. Too “large,” too “Prussian,” too little concerned with the “overall tone of the appearance”—this is how the painter described his elaborate compositions in hindsight.

Composed in the manner of Flemish art of the 17th century: The Small Bric-a-Brac Shop of 1878 recalls the so-called vanitas still lifes of early modern Europe, which pointed to the transience of all worldly things. For the modern painter Schuch, however, the allegorical or trompe-l’œil function of the old art mattered less. In his painting he tested the logic of painting itself: How can brushstrokes be placed to reproduce different textures? What effects do subtle gradations of colour achieve?

Schuch was a voracious reader—he read not only novels, but also the latest French debates on art and society. He devoured Jules Champfleury’s Le Réalisme and Émile Zola’s writings on naturalism. He wrestled with their central questions: What is the role of art in society? How does it relate to reality? In his notes, he tried to distill these theories into his own terms: “Naturalism embraces every subject in the sphere of natural imagination. Realism confines itself to what is personally experienced, directly seen.”

Summer in Nature

Summer meant landscapes! After the winters in Venice, Schuch headed out during the warm months—to the Puster Valley in Austria, across northern Italy, or into Brandenburg. All the painstaking studies he made indoors were, in the end, preparation for what he truly loved: painting natural surroundings.

“I must be in the midst of the nature I paint, so I can study it at every moment—walking, searching, looking, living in it, letting it sink into me until I become part of it. True landscape painting, especially as we understand it today, demands this intimacy.”

Sandy soils, mixed forests, and lakeside villages: Between 1879 and 1881, Schuch spent his summers in Brandenburg, in villages like Ferch on Lake Schwielowsee and Kähnsdorf on Lake Seddin, not far from the growing metropolis of Berlin.

Observed with care, but never bogged down in detail: Schuch’s paintings capture the characteristic buildings, colours, and atmosphere of the Brandenburg landscape. Some of the paintings reveal an orientation towards French models.

Schuch’s Runoff Ditch at Kähnsdorf, for instance, shows his admiration for French painters like Charles-François Daubigny, whose lock and canal scenes Schuch had likely studied in Paris.

Sluices and locks bear witness to water techniques that are thousands of years old—and they, too, shape the character of a landscape. Schuch was intent on experiencing the natural environment he chose for his pictures in depth and often painted en plein air, in the midst of nature.

For Schuch’s landscapes the same holds true as for his still lifes: he did not simply copy what he saw but carefully rendered it with artistic means. Every dab of paint, every brushstroke was consciously placed, left visible, yet forms part of a harmonious and convincing whole.

In his final months in Venice, Schuch studied extensively the changes of colours in sunlight and, in summer, painted the play of light and shadow outdoors.

In his painting Saw Pit from the summer of 1880, Schuch translates the patches of light into radiant ochre and orange tones. He applies the colour generously onto the canvas without blending it with the brush. Schuch thus “materializes” the effect of sunlight.

“It was the French who first realized that the life of the landscape consists in light and air, in the atmospheric conditions which, when translated into art, give the prevailing tone, the mood of the picture.”

Recreating light effects, colour harmonies, and the mood of a landscape — French art remained Schuch’s enduring inspiration. Ultimately, it drew him away from Venice to Paris, the then epicenter of the art world.

Schuch

in Paris

The heart of cultural modernity! By 1882 Carl Schuch was no longer observing France from afar—he was living at its center. For more than a decade, until 1894, he immersed himself in the artistic life of Paris.

“Venice made me very ill: Paris is the climatic resort of the spirit.“

Paris in the late 19th century was the hub of the world’s most innovative art movements. Impressionism, once ridiculed, had already broken through, and newer forms of modern art were emerging in a city undergoing rapid change.

“An artist has no home in Europe except in Paris“ — so declared Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) in 1888. At the time, the city’s art scene and art market were unmatched anywhere in the world. Carl Schuch took full advantage of this vibrant environment: he visited the Salon des artistes français, a major exhibition of contemporary art and the annual highlight of the Parisian art calendar. He also attended auctions at the Hôtel Drouot, the city’s central hub for the art trade. In the influential galleries of Charles Sedelmeyer, Paul Durand-Ruel, and Georges Petit, he saw exhibitions that included works by the Impressionists, among others.

Colour Play

Loose, visible brushstrokes, colours set boldly side by side—Schuch engaged deeply with Impressionist painting, especially admiring the works of Édouard Manet (1832–1883) and Claude Monet (1840–1926).

“In Impressionism there is an attempt to arrive at a stricter vision in colour and a truer effect of nature—that is the spark.”

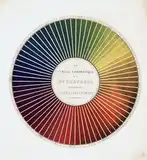

Red against green, or blue against orange — strong complementary contrasts filled the works of the Paris painters. Each of the three primary colours — red, yellow, and blue — has, as the mixture of the other two, a complementary counterpart, producing for the human eye a particularly powerful contrast. From the mid-19th century onward, theorists and scientists devoted themselves intensively to the laws of colour. The writings of the chemist Eugène Chevreul were especially influential in artistic circles. Chevreul also defined the principle of simultaneous contrast: when two colours are perceived directly side by side, they affect each other’s impact. Schuch and his contemporaries drew upon these insights from colour theory in shaping the palette of their works.

Flowers captured with loose, brisk brushstrokes — the painting Peonies, Beakers of Silver and Glass reveals Schuch’s engagement with Impressionist art. Yet while the painters of Impressionism translated natural light directly into unmixed, luminous colours, Schuch tempered many of his hues before applying them to the canvas.

“However many colours one mixes together, the basic tone must always re-enter, restrain, harmonize, unify, and relate everything to itself.”

Bold colour contrasts as the starting point of a painting! — yet unlike the Impressionists, Schuch wove these into a colour fabric of subtle gradations and interrelations. A “neutral ground” — in this work the white napkin and the pewter plate — serves to heighten the interplay of the many shades. From 1885 onward, Schuch referred to such carefully composed paintings as a “colouristic act.”

In 1886, Schuch witnessed the first exhibition of Georges Seurat’s (1859–1891) A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte in Paris. Today celebrated as a masterpiece, the painting quickly became the talk of the town: composed of densely placed, multicoloured dots and strokes, it astonished viewers. The human eye itself has to complete the image, blending the specks into forms and tones. With this sensational work, Neo-Impressionism was born. Its followers painted according to rigorous formal principles: they not only immersed themselves in the colour-theoretical literature of their time, but were also well acquainted with the latest studies in sensory physiology. Scientific insights into vision and human perception shaped the very foundations of their art.

Against discipleship! Schuch was intrigued by the artistic currents of 1880s Paris, with all their artistic and theoretical ambitions, yet he declined to follow them. From Impressionism he drew inspiration, but he forged his own path and his own solutions.

“(…) already Impressionism is trampling out the spark it once had—each one trying to outdo the other in manner instead of in spirit and self-searching.”

A vision of his own

An artist must follow his own path — this principle guided Schuch throughout his life. Vision itself, he believed, was subjective—something his contemporaries in science were also beginning to affirm. Schuch shared with his Parisian contemporaries a deep interest in questions of optics and sensory physiology.

“Every human being is unique and exists only once.”

By the late 19th century, the idea of vision as something stable and objective was being dismantled. Physiologists and early neuroscientists showed that what we see is shaped as much by the body and mind as by the outside world. The eye does not simply record; it compares incoming stimuli with memory and prior experience. Schuch and his fellow artists in Paris followed these developments closely.

Not isolated paintings, but sequences of images — in Paris Schuch continually altered his artistic inventions. At times he changed the arrangement of objects and the play of colours only imperceptibly. From canvas to canvas, Schuch edged closer to a reality whose very appearance is ever in flux.

Not long after his death, critics began comparing Carl Schuch with Paul Cézanne, the “forefather of modern art.” Whether they ever met in Paris remains uncertain, but their approaches resonate. In contrast to the Impressionists, who sought to capture the fleeting impression of nature, both artists pursued a deeper pictorial inquiry: how can a painting be shaped so as to reflect both the laws of the world and the singularity of perception? What, amid all transience, is the inner coherence of the visible world? In seeking answers to these questions, Schuch and Cézanne each forged a pictorial language that was wholly their own.

In Schuch’s work, the artist’s hand and mind is always visible: objects shifted, brushstrokes boldly declared. For him, what mattered was temperament—the unique sensitivity of the painter.

“What shapes artistic expression is not only the how (the individual manner), but also the intensity of feeling.”

Delicate, melancholic, and somber — some of Schuch’s still lifes from his Paris years recall musical pieces in a minor key. These paintings, like those of his contemporary Antoine Vollon, share an undertone of sadness. They convey a profound pensiveness, standing in marked contrast to the fleeting brightness of Impressionist colour.

At times it is worth looking beneath the surface of a painting: X-ray analysis has revealed hidden layers within Schuch’s Ginger Jar with Pewter Jug and Plate. Beneath the visible composition lie earlier arrangements that the artist painted over and transformed. What first depicted a tin can, garlic, and fruit became a pewter jug, a plate, and a rectangular basket. Finally, Schuch shifted the jug to the right and introduced the ginger jar. Not only in his sequences of paintings, but even on a single canvas, Schuch worked tirelessly to explore ever-new pictorial constellations.

„[An artwork] is a frgament of truth seen through a temperament.“

Schuch

in Essence

Exploring and bearing witness to the visible world—Carl Schuch’s true calling remained landscape painting. Even during his twelve years in Paris, he spent his summers out in nature. In the Franche-Comté, on the edge of the Jura Mountains, he created some of his most captivating landscapes.

“For me, the only thing that truly matters in a landscape is colour.”

Stones in the riverbed of the Doubs — a simple scene commanded Schuch’s painterly devotion. What drew him to the Franche-Comté, the homeland of his exemplar Gustave Courbet, were not spectacular panoramas or dramatic natural formations. From 1886 onward, Schuch spent seven or eight summers in the Franche-Comté, along the French-Swiss border.

In his landscapes, Schuch applied what he had tested in his still lifes: he painted certain sections of scenery repeatedly, as sequences of images. How does the structure of a picture change under shifting conditions of light and weather? Which sensations are carried along with it? And what is — despite all transience — the underlying coherence of visible nature?

Secrets of nature

At first glance, Schuch’s landscapes may appear conventional—gentle tones, balanced compositions, atmospheric beauty. But the closer one looks, the more restless and dynamic they become. His brushwork reveals an intensity beneath the surface, suggesting that he aimed not just to represent nature but to probe its inner structure.

“We must paint our pictures deeper than nature itself (…).”

An old sawmill by the river, water rushing over ancient rocks: through light, colour, and form, Schuch created deeply moving, atmospheric images. His woven layers of brushstrokes seem at times to penetrate nature’s very fabric, as if painting could touch upon its hidden structures and invisible connections.

This painting was not created by Carl Schuch but by Gustave Courbet. It depicts the source of the River Loue near Courbet’s birthplace of Ornans. His landscapes of home oscillate between symbolism and natural description. As images of origin, they embody geological conceptions of deep time: strata of rock and coursing waters bear witness to the formation of the landscape over millions of years. At the edge of the Jura mountains, Schuch followed in Courbet’s footsteps.

Layer upon layer of paint — with his palette knife, a kind of painter’s spatula, Gustave Courbet recreated on canvas the cliffs and rock strata of the Jura landscape. His unconventional technique provoked both ridicule and admiration: his depiction of the Roche Pourrie (“rotten rock”) was even commissioned by the geologist Jules Marcou (1824–1898), who marveled at Courbet’s precision in rendering geological formations. Courbet included his friend in the painting itself, as a tiny, barely discernible figure. In the 19th century, theories of rock formation and mountain building were being developed systematically for the first time. The realization that rock masses shift and change over millions of years, bearing within them the deep time of the Earth, inspired awe in many observers—not least in Courbet.

How can the structures of stone be captured in a painting? Schuch looked to Courbet’s palette-knife technique in order to render the rocks of the Jura. With the knife he built up and shaped the paint, layering it across the canvas.

Schuch’s depictions of the rapids of the River Doubs possess an almost intangible quality: the forms of nature dissolve into fascinating modulations of colour, while spatial order blurs. Schuch once wrote that through his art he sought to capture something essential in the harmony of colours — to convey, by means of painting, the “ethereal essence of appearance.”

To modern ears, Schuch’s phrase “ethereal essence” may sound esoteric. In the 1880s, however, the term belonged to the vocabulary of physics. The notion of an ether — an invisible, all-pervading medium — was part of the scientific worldview. Since the 17th century, the theory of ether, imagined as an elastic, malleable substance, had repeatedly been invoked to explain the propagation of waves. Schuch was likely familiar with the idea that ether — as a medium permeating all space — carried electromagnetic waves, above all light, and thus governed the appearance of the visible world. Only with Albert Einstein’s (1879–1955) theory of special relativity did the ether hypothesis lose its validity in the early 20th century.

“Tone has the task of stripping things of their material weight, holding onto only the ethereal essence of their appearance.”

Carl Schuch — a profound and fascinating artist, well worth rediscovering! To encounter his paintings in the original, and to linger before them, is to be carried away. Created in an era of sweeping change, his works reveal the deep beauty of our world. They invite us to savor, to reflect, and to marvel.

Eye catcher

At times Schuch even worked on monumental scale: one of his landscapes from the Franche-Comté stretches nearly two meters across. It has been called the “pinnacle” of his art—a work that overwhelms with its luminosity and the sheer density and depth of its painted surface. Only when standing before the canvas itself can one truly grasp its beauty.